Travel Direction as a Fundamental Component of Navigation

With Elizabeth R. Chrastil, Sam Ling, and Chantal Stern

Imagine you are walking to a Starbucks, you can hear birds singing in the trees, and feel the breeze touch your skin. Suddenly, you notice a bunny running by. You turn your head to follow the bunny running and hiding into a nearby bush, while your feet are still walking toward your destination. In this case, where you are facing toward and where you are moving toward are both part of your sense of direction, but they represent different pieces of spatial information.

Head direction refers to where someone is facing toward, while travel direction refers to the direction of one’s body movement. In daily life, people usually conflate the two directions, thinking that where we are facing toward is where we are going. However, as you have seen in the bunny example, these two factors represent distinct pieces of information. Extensive studies have examined head direction cells that fire when someone faces a particular direction and found them to be a crucial part of navigation. However, it is unclear whether travel direction plays a primary role in the internal representation system of navigation.

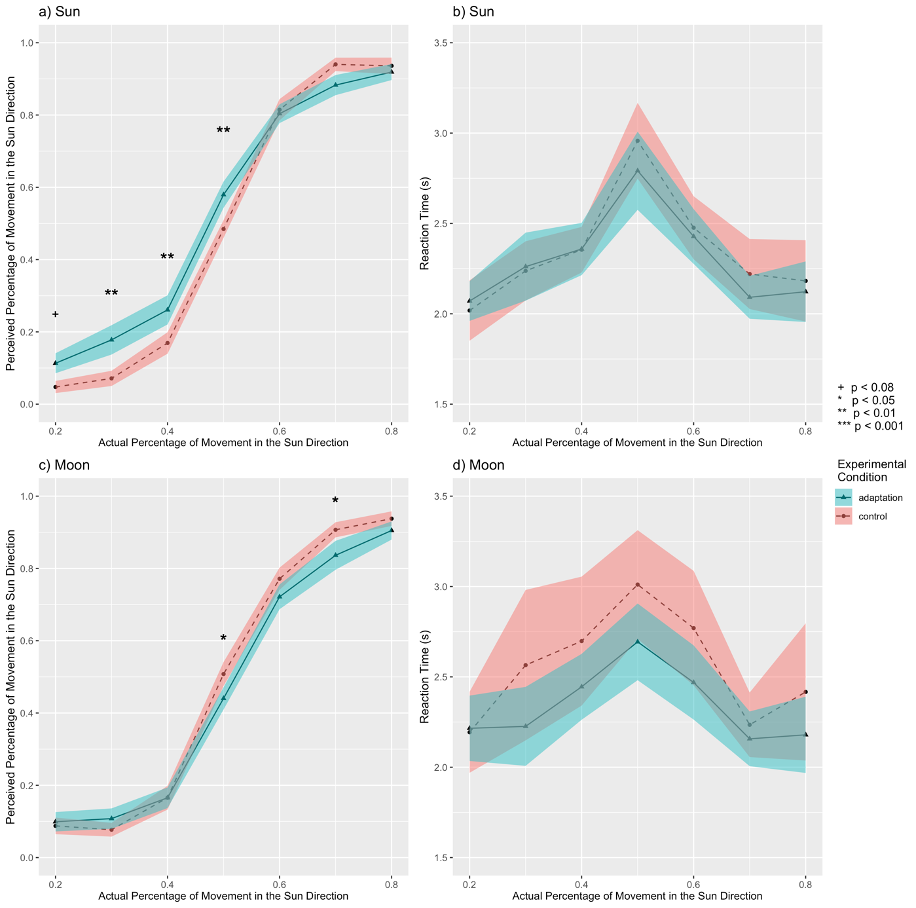

To test whether travel direction is a fundamental component of human navigation, we asked people to sit in front of a computer and to move around in a virtual hallway, in a way that resembled playing a computer game. In this experimental setting, we dissociated travel direction from head direction by flipping the head direction occasionally while maintaining the same travel direction. We then tested sensitivity to travel direction by letting people become accustomed to visual motion in a certain direction–a motion adaptation paradigm. Here are the results for the control condition, shown in red, and the adaptation condition, shown in blue. We found a difference between the people’s report of the net change of travel direction in the adaptation condition and in the control condition, as you can see in the difference between the two lines. The results indicate a motion aftereffect of travel direction, suggesting that travel direction is a fundamental component of human navigation. Interestingly, subjects had a higher frequency of reporting net travel toward the adapted direction, indicating that the aftereffect is opposite to the traditional motion aftereffect.